Jesus Film Project® understands the value of expressing Jesus’ story creatively. Today, we use film to communicate the gospel story visually, but there was a time when artists relied on paintings to share Jesus’ majesty with others. For powerful quotes from Jesus, read this.

We’ve collected 15 of the most famous and essential paintings of Jesus from many different artists and across many time periods. Let’s look at how artists have pictured Jesus within their cultural context.

1. Christ Pantocrator

Year: 537 AD

Style: Iconography

Location: Hagia Sophia, Istanbul

This Jesus painting is currently in Instanbul. The Hagia Sophia (Holy Wisdom) Cathedral was at the heart of the Byzantine Empire. Emperor Justinian considered it the crown jewel of Constantinople. It housed antiquity’s largest enclosed space and a vast dome. The interior was decorated in intricately carved marble and beautiful mosaics, of which Christ Pantocrator is one. Typically translated as “almighty” or “all-powerful,” the word Pantocrator literally means “ruler of all.”

2. Ognissanti Madonna — Giotto di Bondone

Year: 1310

Style: Gothic

Location: Uffizi Gallery, Florence

This altarpiece, painted for the Florentine Church of Ognissanti, had a profound impact on religious art. Older Byzantine styles were often two-dimensional and rigid. They didn’t make much of a connection to the viewer. Giotto di Bondone ushered in a form that was more human and less flat. Without Giotto’s work, we may have never had the Renaissance movement.

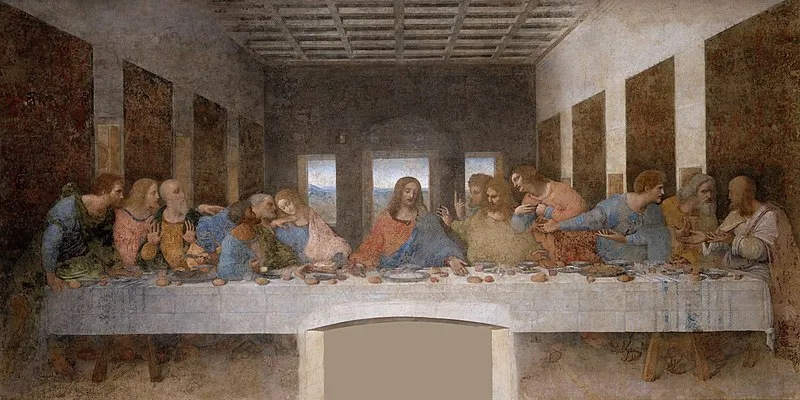

3. The Last Supper — Leonardo Da Vinci

Year: 1495–1498

Movement: High Renaissance

Location: Santa Maria delle Grazie, Milan

Da Vinci’s The Last Supper is probably the most important mural painting in the history of the world. The Dominican monastery of Santa Maria delle Grazie has been declared a World Heritage site as a “unique artistic achievement, of an exceptional universal value that transcends all historical contingencies.”

Da Vinci did scores of preparatory sketches before applying brush to the wall of the dining room of the Santa Maria delle Grazie. Using a nail and string, Da Vinci placed the vanishing point directly behind Jesus’ head so that the table ends, ceiling squares and all other parallel lines are geometrically aligned.

This Jesus painting is so familiar and famous that many have assumed that details of the painting include secrets or reveal clues to elaborate conspiracy theories. While they’re all incredibly off-base, these theories point to the everlasting cultural influence of this painting.

4. Salvator Mundi — Leonardo da Vinci

Year: 1499–1510

Movement: High Renaissance

Location: Louvre, Abu Dhabi

In 2017, Salvator Mundi was sold by Christie’s in New York for $450.3 million, the most expensive painting ever sold at a public auction. Despite the fact that this painting sold for such a high price, there is quite a bit of controversy around its origin.

Purchased in 2005 by two art dealers in New Orleans, no one recognized the work as a da Vinci. Worms had infected the wood support; at one point, it had been inadequately restored and overpainted. The overpainting was stripped away, missing sections were restored, and the investors believed they had a da Vinci painting in their hands. After years of analysis and research, it was included as a lost original in a Leonardo da Vinci exhibit at London’s National Gallery in 2011—although some specialists still dispute that it is a da Vinci.

The Jesus painting depicts Jesus Christ in Renaissance garb, holding His fingers in a benediction. In his other hand, He holds a crystal orb representing heaven’s celestial sphere, signifying that He is the Salvator Mundi (Savior of the World).

5. The Transfiguration — Raphael

Year: 1516–1520

Movement: High Renaissance

Location: Pinacoteca Vaticana, Vatican City

Known throughout the world as Raphael, Raffaello Sanzio da Urbino was an Italian High Renaissance artist. High Renaissance found its peak from 1490–1527, revolving around three primary figures: da Vinci, Michelangelo and Raphael.

This Jesus painting was commissioned by Cardinal Giulio de Medici, who would later become Pope Clement VII. Raphael began work on the painting in 1516; the painting was finished in 1520, the same year of Raphael’s death. There is some speculation that two of Raphael’s students completed a couple of the figures in the painting’s lower right, but there is no conclusive evidence.

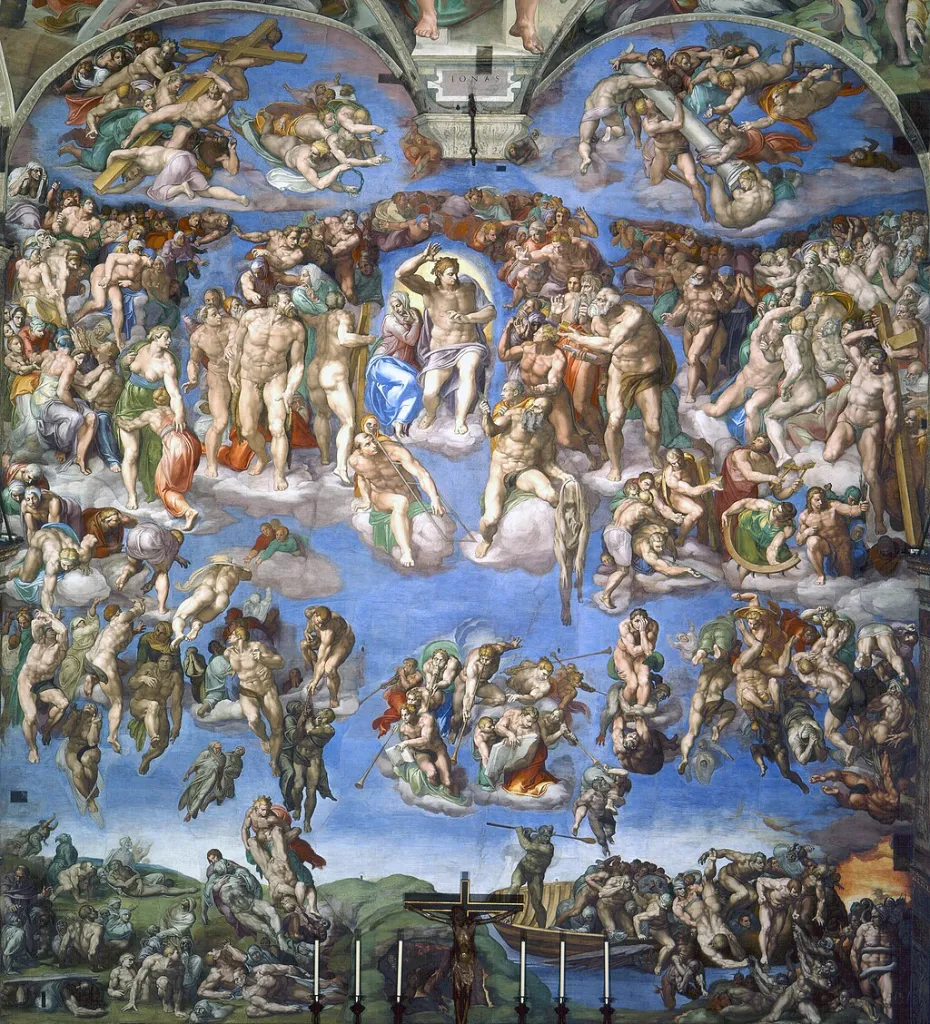

6. The Last Judgment — Michelangelo

Year: 1536–1541

Movement: High Renaissance

Location: Sistine Chapel, Vatican City

Pope Julius II commissioned Michaelangelo to paint the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Upon completing the ceiling, Michelangelo returned to create the large fresco, which would become The Last Judgment.

As the title suggests, this painting of Jesus depicts the final judgment of humanity. Jesus is the centerpiece of this painting, arm raised, announcing His judgment. On His right are those destined for the kingdom, and on His left are the condemned.

When the piece was unveiled, it received a mixed response. The Roman agent of Cardinal Gonzaga of Mantua reported: “The work is of such beauty that your excellency can imagine that there is no lack of those who condemn it. . . . [T]o my mind it is a work unlike any other to be seen anywhere.” Others didn’t share this enthusiasm.

Many were scandalized by the painting’s nudity and the inclusion of mythological figures like Charon and Minos. Many argued that Michaelangelo was more interested in showing off his abilities than portraying simple, sacred truths. Other artists were hired to paint over some of the forms with drapery and fig leaves.

7. Christ Carrying the Cross — El Greco

Year: 1580

Movement: Mannerism

Location: Metropolitan Museum of Art

Toward the end of the High Renaissance, Mannerism became a movement throughout European art. Mannerism featured a flattening of the pictorial space, providing little depth or perspective and ambiguous space. Mannerism also distorted human figures, providing staged, awkward poses, and utilized a limited color palette.

El Greco’s Christ Carrying the Cross includes no other characters or background images. This Jesus painting focuses on Jesus’ willingness to sacrifice Himself for humanity. He gently embraces the cross and looks resignedly toward heaven. You can see the impact of Mannerism in Jesus’ eyes, which are almost oversized to emphasize the tears and instill a feeling of drama.

8. Supper of Emmaus — Caravaggio

Year: 1601

Movement: Baroque

Location: National Gallery, London

Mannerism gave way to Baroque art which is full of dark backgrounds, deep colors, dramatic light and sharp shadows. All of these characteristics can be seen in Caravaggio’s Supper of Emmaus. The painting of Jesus depicts the moment that Jesus breaks the bread and the Emmaus travelers recognize Him as the resurrected Messiah (Luke 24:13–35).

Caravaggio’s use of dark colors instills the image with a powerful sense of drama. By placing the actors before a wall that seems to only be inches away from them, he distorts the viewer’s sense of distance and proportion, encouraging the viewer to see themselves in the same space.

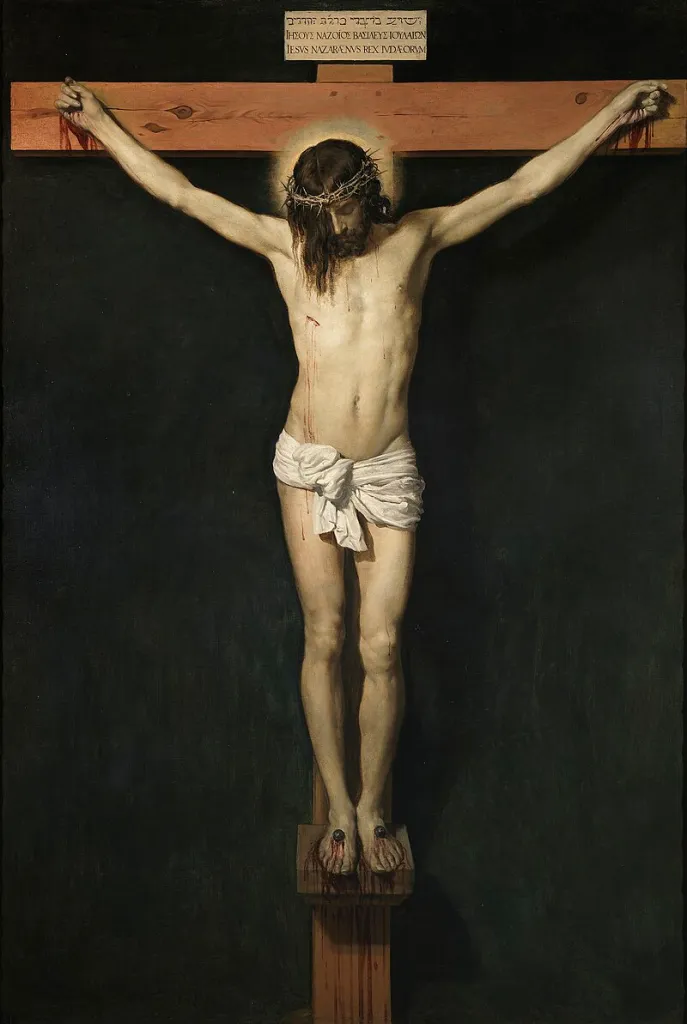

9. Christ Crucified — Diego Velázquez

Year: 1632

Movement: Baroque

Location: Museo del Prado, Madrid

Another remarkable example of the Baroque movement is Diego Velázquez’ Christ Crucified. In this Spanish painting, Jesus’ pale complexion is contrasted against a dark background. Velázquez doesn’t focus on the agony of the cross. Instead, He paints Jesus unadorned, the only thing giving away His divine identity is the halo around His head.

It is believed that this Jesus painting was commissioned after Velázquez was cleared following an investigation by Inquisitors. The Spanish Inquisition was a result of a fear that the Jewish population was growing more powerful in Spain and marginalizing Christians. In 1478, a papal bull was decreed allowing Catholic monarchs to enforce religious conformity and expel Jews from Spain. Velázquez was accused of aligning with Jewish bankers over Genoese ones.

It’s believed that Jerónimo de Villanueva, the founder of the Convent of San Plácido, commissioned the work as a demonstration of Velázquez’ piety.

10. The Storm on the Sea of Galilee — Rembrandt

Year: 1633

Movement: Dutch Golden Age

Location: Whereabouts unknown since 1990

The Dutch Golden Age shares a lot with the Baroque period. Not only do they share the same time period, but they also share many characteristics, including the use of shadows and drama. The Dutch Golden Age is marked by richness, movement and tension.

On March 18, 1990, two thieves posing as police officers entered Boston’s Stewart Gardner Museum pretending to respond to a security threat. The museum staff was tied up, and the thieves made away with around $500 million worth of stolen art from the likes of Manet, Degas and Vermeer. Among them was Rembrandt’s work. Unfortunately, none of these works have been retrieved.

11. Head of Christ — Rembrandt

Year: 1640s

Movement: Dutch Golden Age

Location: Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

Up to this point, paintings of Jesus had strong religious qualities. The Lord was depicted as majestic and otherworldly. Many artists were afraid that painting Jesus Christ in a way that was too human would make it difficult to receive church commissions.

It hardly seems revolutionary at this point, but Rembrandt’s focus on Jesus’ humanity was a huge game changer. Rembrandt’s Jesus is painted without a halo or other religious imagery. The Lord doesn’t look directly at the viewer, instead, He stares off pensively. The background features zero religious context. There are no symbols or imagery suggesting this comes from a biblical narrative. We’re left with an image of Jesus that’s full of both humanity and mystery.

12. Ecce Homo by Antonio Ciseri

Year: 1871

Movement: Italian Purism

Location: Gallery of Modern Art, Pitti Palace

This painting of Jesus is in Florence, Italy. Antonio Ciseri was an Italian painter born in Ronco, Switzerland. He was highly influenced by the Purismo movement, which rejected Neoclassicism and focused on artists like Raphael. You can see Raphael’s influence in Ciseri’s figures. But Ciseri’s paintings have an almost cinematic, photo-like realism.

In Ecce Homo (meaning “behold the man”), Pilate speaks to the crowds, finding no fault in Jesus. As one looks at the light, the draping fabric, and the movement and realism of the characters, it looks like a still from a movie. A lot of that effect is achieved through the choice to paint this scene from the back instead of straight on like many artists would choose to set up this shot, giving the viewer the feeling of being a silent spectator.

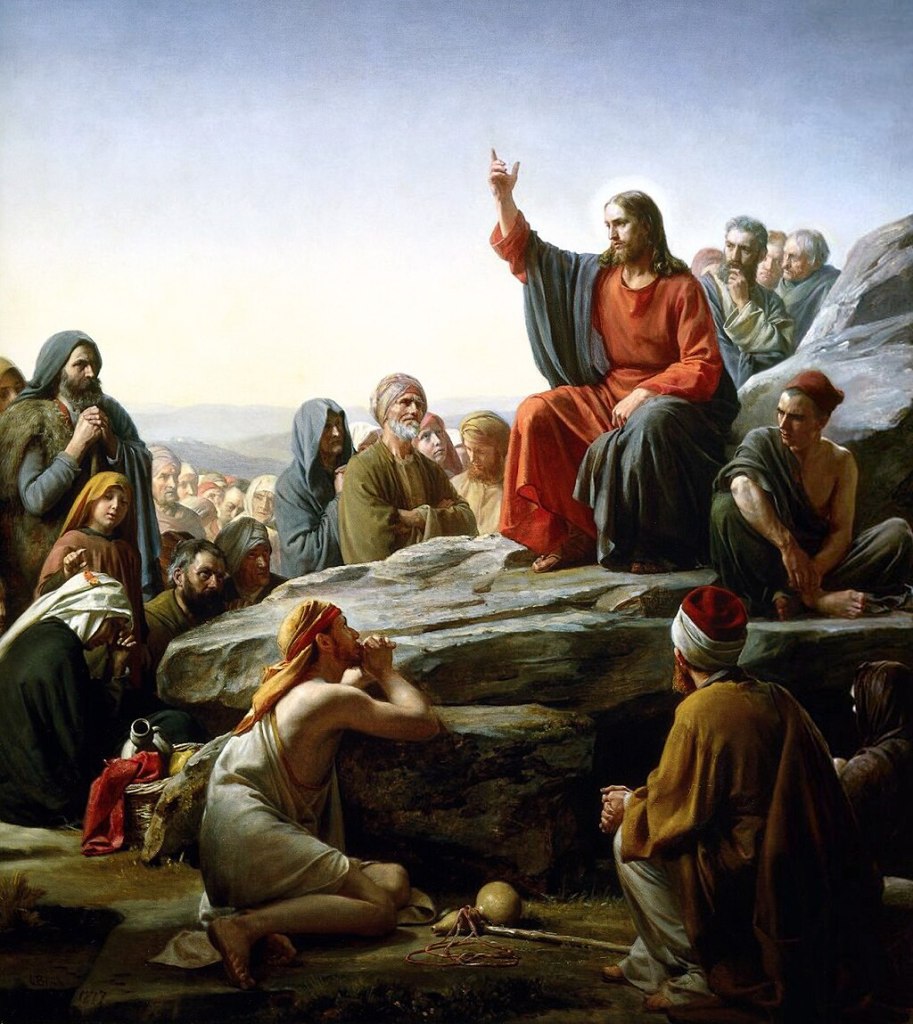

13. Sermon on the Mount — Carl Heinrich Bloch

Year: 1877

Location: Museum of National History at Frederiksborg Castle

Anyone raised in the Christian church is likely familiar with the work of Carl Bloch. His artwork has been used in Sunday School classes and children’s Bibles for decades. Although he is known for his biblically inspired paintings, he also painted many rural daily-life scenes. And unlike many artists, he became famous fairly early in his life.

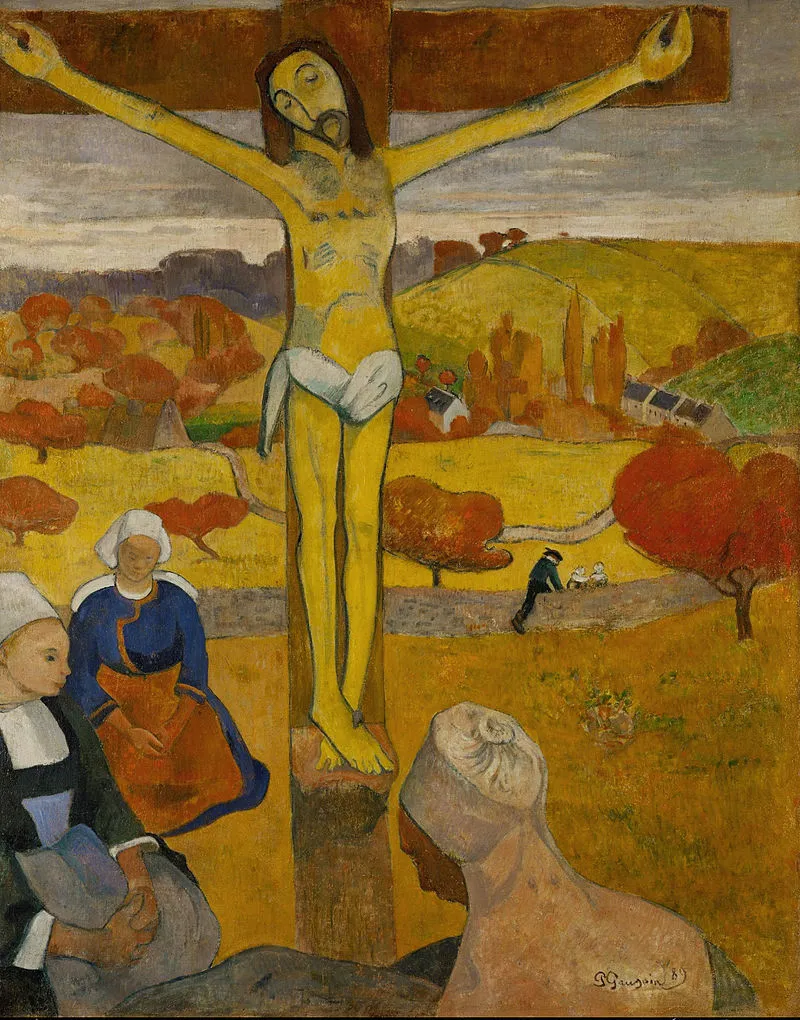

14. The Yellow Christ — Paul Gauguin

Year: 1889

Movement: Symbolist

Location: Albright-Knox Art Gallery, Buffalo, NY

The symbolism movement sought to reflect emotions and ideas rather than reflect the natural world. This means that they used metaphors and symbols rather than realistic imagery to communicate with the viewer. Most Symbolists painted in wide strokes of unmodulated color to fashion flat and abstract figures and forms.

With Le Christ Jaune (The Yellow Christ) Gauguin used a representation of a 17th-century painted crucifix that hung in the Trémalo Chapel. The subject of the painting was actually the peasants kneeling before the crucifix. Gauguin wanted to portray the isolation and piety of the local peasantry in Pont-Aven France where he was visiting.

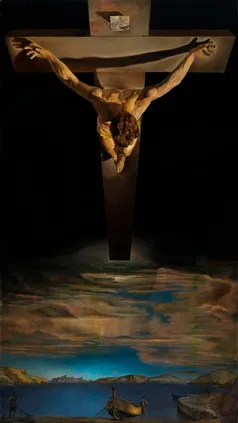

15. Christ of Saint John of the Cross — Salvatore Dali

Year: 1951

Movement: Surrealism

Location: Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow

Surrealism sought to revolutionize human experience by combining reality with the unexpected and bizarre, giving power to the unconscious mind, and completely disregarding conventional expectations. It featured things like dream-like imagery, visual puns, distorted figures and biomorphic shapes.

Salvatore Dali’s Christ of Saint John of the Cross came out of a dream where he saw Christ’s crucifixion from God’s perspective. There are no wounds, thorns or agony present. The scene at the bottom of the image featuring a moored boat and still water adds to this image’s feeling of tranquility and peace. As God watches the crucifixion unfold, there is a sense of silence and wonder of God’s salvific handiwork being manifested.

Experience Jesus’ story in new ways

For many centuries, mosaics, frescos and paintings were the ideal way for creatives to visually communicate the wonder and power of Jesus’ story. Today films are a powerful tool for communicating the gospel in a compelling and visual way. People get to see a representation of Jesus’ ministry and hear the story told in their own heart language.

If you’re interested in discovering how Jesus’ story is being told in film, check out our watch page. You’ll find a number of gospel-related films to help you re-experience the life of Jesus and start conversations with the people around you.