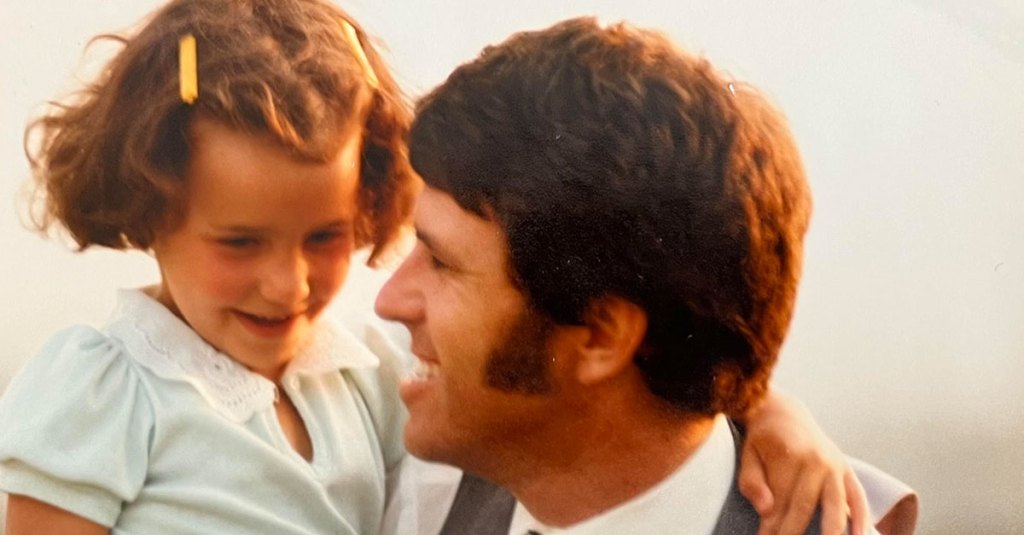

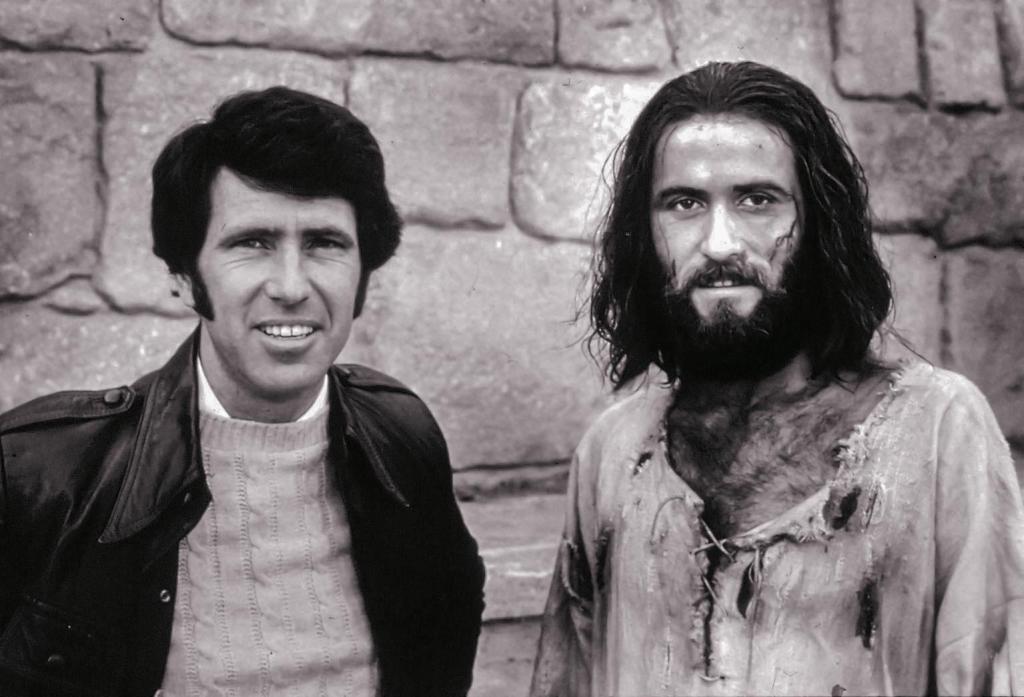

In the 1950s, Bill Bright, the founder of Campus Crusade for ChristⓇ (now known as CruⓇ in the U.S.), envisioned creating a film about the life of Jesus. That vision became a reality thirty years later when my father, Paul Eshleman, launched the JESUS film and founded Jesus Film ProjectⓇ shortly after.

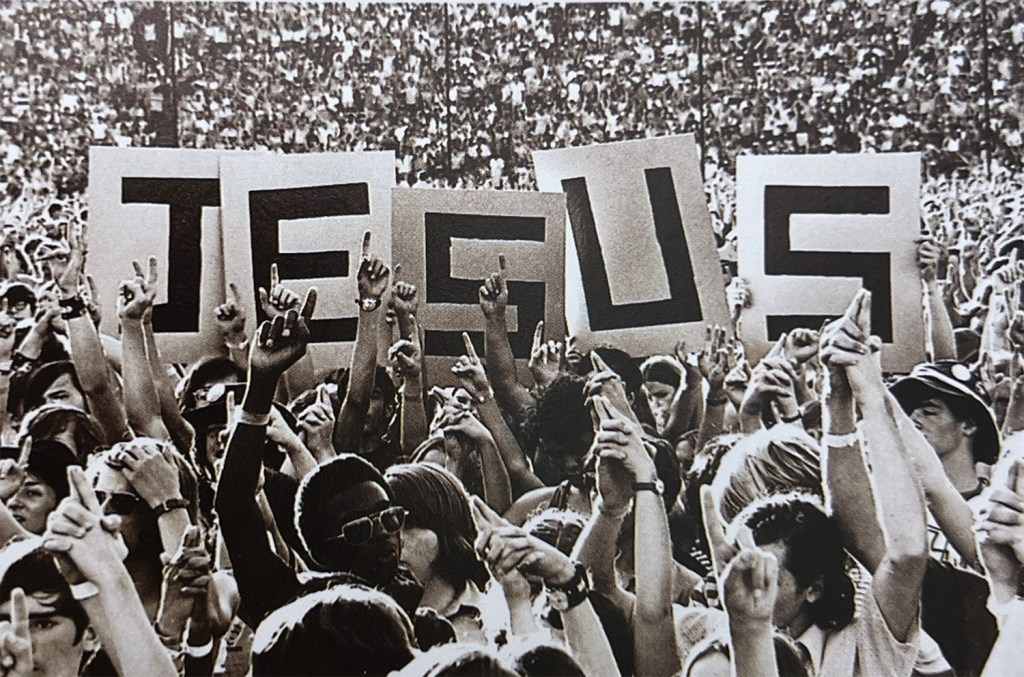

Today, the JESUS film is the most translated film in the world. And by God’s grace, Jesus Film Project has accomplished another astounding milestone: the film’s 2,200th translation in Kulango, Bouna—a language spoken in Côte d’Ivoire.

This mission to share the gospel with the world through film was a vision my father deeply believed in and dedicated his life to fulfilling. Just as the Shepherd leaves the 99 to search for the one lost sheep (Matthew 18:12), my father believed everyone deserved to hear about Jesus in a way that speaks directly to their hearts.

That dedication shaped not only the JESUS film, but also the trajectory of my own life and faith.

Why Numbers Matter in Sharing the Gospel

My father loved two things in equal measure: statistics and stories. Numbers mattered to him because they represented people—real individuals with the opportunity to hear about Jesus for the first time. He quoted populations and language details off the top of his head, but it wasn’t about the data alone. He lived and breathed for the stories: lives changed, faith renewed, and people encountering Jesus for the first time.

Matthew 24:14 shaped my father’s legacy: “And this gospel of the kingdom will be preached in the whole world as a testimony to all nations, and then the end will come” (New International Version).

He often shared this favorite verse as a reminder to reach every lost lamb in every unengaged and unreached people group, ensuring everyone had the opportunity to know Jesus.

Jesus Speaks My Language

The heart of the JESUS film lies in its meticulous attention to cultural and linguistic detail. My father believed that hearing Jesus speak your heart language communicates something profound: Jesus sees and knows you.

For so many who have never before heard the gospel in their language, it’s not just a movie– it’s an encounter with Jesus.

Many of the stories in my father’s book, I Just Saw JESUS, perfectly capture this. For so many who have never before heard the gospel in their language, it’s not just a movie—it’s an encounter with Jesus.

I share two such stories at the end of this blog.

The Ongoing Mission to Reach the Unreached with JESUS

As we celebrate the 2,200th language of the JESUS film, it’s clear that the mission is far from over. My father often carried lists of unreached people groups, asking, “Who are we missing? How can we reach them?” He believed deeply in the urgency of the Great Commission and often reminded us that every person matters to God.

In honor of my father, I’d like to share a couple of stories—excerpts from his recently re-released book I Just Saw JESUS. These stories are glimpses into the way God has used this film to impact the world.

Missionary Story from I Just Saw JESUS: The Tarahumaras

In the hillside clearing, two hundred men, women, and children sat silently watching JESUS, the only film in the world translated into the Tarahumara language. It had taken months of work and $20,000 to complete the project.

The voice of the narrator belonged to Eduardo Lopes. Eduardo, born and raised in the village of Samachique, was no stranger to translation work. In 1942 his father, Ramon, began working with WycliffeⓇ missionary Kenneth Hilton on a translation of the New Testament. Thirty years later, through the tireless labor of Hilton, the first Tarahumara New Testament was printed—but it received a cool reception. Ramon and a few others had accepted Christ, but in a total population of 75,000, Christians numbered less than 100.

In 1975, two years after the New Testaments arrived, deteriorating health forced Hilton to leave the tribe. Nearly ten years later Eric and Terri Powell, field staff members with the Navajo Gospel Mission, initiated the Tarahumara film production based on Hilton’s work. Jim Bowman, a businessman with film background from Tucson, Arizona, traveled to Samachique in August 1984 and recorded the narration track with Eduardo and Ramon, promising to return with the completed film and a team to show it in the mountain villages.

“For the first time I understand what Jesus did for us.”

Ramon was skeptical. He had pastored the local church for many years and seen North Americans come and go. Most of their promises of help and materials had not been kept, and when eight silent months passed after he and his son recorded the soundtrack, he began to believe the JESUS film would never reach their village. When the film team finally did arrive in Samachique, Ramon was distant and reserved.

Now as the crowd watched the film under the star-filled Mexican sky, team members scanned the faces, looking for responses. The people were visibly shaken by the cruelty and pain they witnessed as Jesus was put to death on the cross. One man became physically ill. The burial scenes seemed to impress them, and the team learned later that the Tarahumara fear death deeply, sending their dead to the afterlife with days of elaborate ceremonies. They saw many similarities between their burial customs and the Jewish ways in Jesus’ time.

When the film ended, Ramon asked those interested in knowing more about Jesus to come to the lights stretched across the front of the film site. Christians in the group were praying for those they knew needed Christ, but no one came. Finally, deeply disappointed that no one responded to the message, Ramon watched as the crowd wandered off into the darkness.

Everyone left except a few who clustered around the fires the team built on the edges of the clearing. Twenty-five or 30 Tarahumaras warmed themselves in small groups, talking quietly, as if waiting for something. All of the Christians—those who spoke Tarahumara—left, and team members were forced to speak with the seekers in Spanish. Only a few teenaged boys understood any Spanish, but they stayed, asking questions.

Why had the people not come to the lights when Ramon invited them? It later became very clear that the invitation made them feel singled out. In their culture the only time a person is set apart from the group is for punishment or tribal ostracism. The team adjusted and after other showings of the film, asked people to stay afterward around the fires or to raise their hands if they wanted to know more about receiving Christ.

In the four days they spent with the Tarahumaras, more than 800 viewed the film, with an estimated 95 percent never having heard the gospel before. More than 80 responded to the message.

During the day the people returned to talk with the team about spiritual things. One young man who watched the film said he had not slept all night—he did not know what to do with Jesus. Others asked where the people came from who killed Jesus, and one wanted answers about the sacrifice Jesus made for us. Jim Bowman asked him about the sacrifices he made.

“I must offer goats and chickens to Onoruame so that my crops will not fail and God will not be angry with me,” he said.

“That’s what Jesus has done for us,” Jim said. “He was the last sacrifice needed for all men, for all time.”

The young man nodded, and a smile spread across his face. “I understand,” he said. “For the first time I understand what Jesus did for us.”

In Choquita, a Spanish-speaking Mexican missionary hosted a showing of the film and was thrilled to see the Tarahumaras he had been trying to communicate with understanding and responding to the message. Ten men raised their hands, indicating they were asking God to forgive their sins.

With each day’s showing of the film, Ramon and the other Christians grew more encouraged. The film opened avenues of distribution for the Tarahumara New Testaments. The foundation laid by Kenneth and Martha Hilton’s sacrificial work now bore new fruit. A few of the older men and many of the young men could read, and JESUS caused questions and created an interest in them that had not existed before. By the time the team packed up their gear and headed homeward, Ramon was making plans for more showings of the JESUS film in other Tarahumara villages.

Missionary Story from I Just Saw JESUS: The Garifunas

It was late, and the moon hung low and bright over the Caribbean as we struggled against the waves threatening to capsize our dugout canoe. Warm winds blew hard through the palms on shore, churning the sea to a tempest while the thirty-five-horsepower outboard strained to pull us through. Several inches of water sloshed around us and our equipment, and I watched the two native boys bail it back over the side as fast as their young arms could manage. There were no oars and no life jackets, and I prayed earnestly that God would get us to shore.

We were headed along the coast of Honduras with missionary David Dickson, bound for a Garifuna village where the gospel had never been shared. JESUS was scheduled to be screened for hundreds of Black Caribs in the language of the Garifuna Indians, and we did not plan to disappoint them. Finally, we headed the canoe toward shore and soon unloaded on an isolated beach.

In a tropical paradise that stretches along the coast of Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and Nicaragua, 100,000 Black Caribs coax their livelihood from the sea as fishermen. Descendants of nineteenth-century black Africans who escaped from slave ships and settled with the Carib Indians, they have been almost overlooked by those with the good news—but not quite. In 1955 a young Wycliffe translator named Lillian Howland went to Central America to begin translation work on the New Testament. Thirty years later she completed the translation, but few Garifunas responded to the gospel. David Dickson heard that she mastered the language and began to study it under her tutelage. He now is the only white man to speak it fluently. As he learned the language, his burden to reach the Garifunas increased. He saw the JESUS film as an opportunity to spread the message quickly.

Not long after, David and two Garifunas left the palm-lined beaches and jungles of Honduras and flew to San Bernardino, California, to dub the film into their language. A few months later our team returned with the film ready to be shown to the Black Caribs.

In one scene Jesus greets a small child with a greeting known only to these people. “What are you doing?” Jesus’ Garifuna voice says.

“Nothing,” the child responds, and the Black Carib audiences break into applause and delighted laughter.

“This man knows Garifuna!” someone says. “He speaks our language. He knows our greeting!”

As the film progressed, Dickson moved among the crowd of two hundred chattering people to hear what they said about the film. When Jesus healed someone, comments like “Look at that! Can you believe that!” were heard.

One woman said to her friend, “Who wouldn’t believe in Jesus? Did you see Him heal that blind man? Anyone would want to believe in Him.”

The Garifunas were especially pleased with scenes that involved the sea and the fisherman’s way of life. They loved watching Peter and the disciples haul straining nets filled with fish into their boats. When Jesus spoke to the winds and calmed the sea, everyone in the audience related to what they saw because all of them had lost family and friends who drowned in angry storms at sea.

They talked throughout the entire film, but the message got through. After the showing, fifteen men and twenty women gathered under the lights to make decisions to trust Christ. On the final evening, the team showed the film in a large village to a crowd of eighteen hundred Garifunas.

Everyone came—drunks, unruly children, even witch doctors performing incantations as the film showed. The Spirit of God is strong enough to meet any challenge, and that night one hundred fifty-five made decisions for Christ.

The need is there—an insatiable hunger for the God of love. Through the film JESUS, the message is being told and understood. On our three-day trip to the Garifunas, two hundred prayed to receive Christ. Churches are being established, disciples are being made, and their faith is being built up.

“Come back,” a Garifuna village chief said. “You must come back again and tell us more about Christ.”

The Garifuna and the Tarahumara Indians have been called “unreached people.” However, the JESUS film may be the key to reaching them and thousands of other groups like them around the world.

Join the Mission

It’s an honor to carry on my father’s legacy, sharing stories of how God continues to move through this incredible project. And as you read these stories—whether from Côte d’Ivoire, the Garifuna people, or beyond—I hope you were inspired to be part of this mission, sharing the message of Jesus with those who still haven’t heard.

You can read more of my dad’s story in I Just Saw JESUS, available now on Amazon.

Learn more about the 2,200th translation of JESUS and why it’s significant in the latest news release on our website. You can download the full story here.

Support Jesus Film Project’s mission to reach everyone, everywhere with the gospel.