Most scholars believe that Jesus’s primary language was Aramaic. There’s strong evidence that most Jews spoke this Semitic language throughout Palestine in the first century. But there’s also reason to believe Jesus was probably familiar with a few languages.

Let’s take a look at the languages that were popular in Jesus’s time and region, and some of the best evidence for the languages Jesus knew.

Wasn’t Hebrew Israel’s primary language?

Many Bible readers would naturally assume that Jesus spoke Hebrew. After all, most of the Old Testament is written in Hebrew. We associate it with the Jews and it is the official language of Israel today. But it’s not that simple. Hebrew’s influence has ebbed and flowed over time.

Throughout the Old Testament, Israel was a nation with a clear identity and purpose. They were set apart from (and often at odds with) the nations around them. They were the only people speaking Hebrew while other languages developed in surrounding nations. Aramaic was one of those languages.

Aramaic is a Semitic language that’s closely related to Hebrew. There was a time when very few Israelites spoke it. Both 2 Kings and Isaiah tell us about a time when the king of Assyria sent some officers to threaten Israel. When they got to the walls of Jerusalem and called for Hezekiah, the king of Israel sent out Eliakim, Shebna, and Joah to speak on his behalf.

The Assyrian field commander wasn’t interested in having a private discussion with Hezekiah’s men. Instead he made threats loudly enough in Hebrew for the Jewish citizens on the wall to hear. The author of 2 Kings tells us what happened next:

Then Eliakim son of Hilkiah, and Shebna and Joah said to the field commander, “Please speak to your servants in Aramaic, since we understand it. Don’t speak to us in Hebrew in the hearing of the people on the wall” (2 Kings 18:26).

Hezekiah’s men didn’t want the Jewish people listening to understand what the commander was saying, so they asked him to speak Aramaic. This tells us that only the most well-educated Israelites spoke Aramaic.

Aramaic takes prominence

Over time, however, Aramaic began to replace Hebrew as the common, everyday language for Israelites. While Hebrew was tied to Israelite identity, Aramaic was an international language of trade throughout Asia Minor during the Assyrian and Babylonian reigns. Jews had to adapt and began using an Aramaic/Hebrew hybrid. This evolved into a universal acceptance of Aramaic for day-to-day living.

Nehemiah laments this shift as he says, “Half of their children spoke the language of Ashdod or the language of one of the other peoples, and did not know how to speak the language of Judah” (Nehemiah 13:24).

Did Jesus speak Hebrew?

The Israelites held onto Hebrew as a religious language used in liturgy and observance. Jesus’s education would have involved a familiarity (if not fluency) with Hebrew. Luke tells us the story of a 12-year-old Jesus sitting at the Temple asking and responding to Jewish teachers, who were amazed at His understanding and answers. Impressing these teachers would have required a familiarity with the law and the prophets, which suggests a working knowledge of Hebrew.

Jesus later inaugurates His ministry this way:

He went to Nazareth, where he had been brought up, and on the Sabbath day he went into the synagogue, as was his custom. He stood up to read, and the scroll of the prophet Isaiah was handed to him. Unrolling it, he found the place where it is written:

“The Spirit of the Lord is on me, because he has anointed me to proclaim good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim freedom for the prisoners and recovery of sight for the blind, to set the oppressed free, to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.”

Then he rolled up the scroll, gave it back to the attendant and sat down. The eyes of everyone in the synagogue were fastened on him. He began by saying to them, “Today this scripture is fulfilled in your hearing” (Luke 4:16-30).

While the Septuagint (the Greek version of the Hebrew Bible) was available at this time, most synagogues would have prided themselves on using Hebrew scrolls. Jesus likely read these words in their original Hebrew.

Did Jesus’s audience speak Hebrew?

Just because Jesus spoke Hebrew doesn’t mean most Jews did. To answer this question, we need to know the primary language of normal citizens in Israel.

As we’ve noted, translation of Hebrew Scriptures into other languages like Greek was happening, but most religious Jewish writing was still done in Hebrew. For example, a lion’s share of the Dead Sea Scrolls were written in Hebrew (with a few Aramaic, Greek, and Arabic texts-and even some Latin fragments).

So while Hebrew would be more familiar among extremely devout Jews, most Israelites would have spoken Aramaic, albeit in their own dialect. For instance, the Gospels demonstrate that Peter had a Galilean dialect that would have been easily identifiable by folks in Jerusalem.

Matthew tells us that when Jesus was being tried, a group in the courtyard outside recognized Peter:

Now Peter was sitting out in the courtyard, and a servant girl came to him. “You also were with Jesus of Galilee,” she said.

But he denied it before them all. “I don’t know what you’re talking about,” he said.

Then he went out to the gateway, where another servant girl saw him and said to the people there, “This fellow was with Jesus of Nazareth.”

He denied it again, with an oath: “I don’t know the man!”

After a little while, those standing there went up to Peter and said, “Surely you are one of them; your accent gives you away.“

Then he began to call down curses, and he swore to them, “I don’t know the man” (Matthew 26:69-74, emphasis added)!

In Mark and Luke’s account, they simply identify Peter by his region, “About an hour later another asserted, ‘Certainly this fellow was with him, for he is a Galilean.‘” (Luke 22:59, emphasis added).

There were some apparent dialects and differences between the Aramaic spoken throughout Galilee and what was spoken in Jerusalem. It’s obvious that they’re speaking the same language here, but Peter’s accusers still recognize that he’s not from around Jerusalem.

This comes up again in Acts:

Now there were staying in Jerusalem God-fearing Jews from every nation under heaven. When they heard this sound, a crowd came together in bewilderment, because each one heard their own language being spoken. Utterly amazed, they asked: “Aren’t all these who are speaking Galileans? Then how is it that each of us hears them in our native language? Parthians, Medes and Elamites; residents of Mesopotamia, Judea and Cappadocia, Pontus and Asia, Phrygia and Pamphylia, Egypt and the parts of Libya near Cyrene; visitors from Rome (both Jews and converts to Judaism); Cretans and Arabs-we hear them declaring the wonders of God in our own tongues!” Amazed and perplexed, they asked one another, “What does this mean” (Acts 2:5-12, emphasis added)?

The disciples weren’t wearing name tags that would identify them as Galilean, so it’s likely that their dialect gave them away.

It’s also pertinent to recognize that Jews from all over would make a pilgrimage to Jerusalem for Pentecost. The people who Luke references here were Jews or converts to Judaism from all over the Near East-and they all spoke different languages. At this point, there wasn’t a monolithic Jewish language.

But didn’t they all speak Greek?

Since the New Testament was written in Greek, it makes sense to assume that most people spoke Greek. Right?

As Alexander the Great’s armies moved East in the 300s BC, Macedonia paved the way for the expansion of Greek thought and culture. Greek culture was at its zenith, while nations like Egypt and Israel were waning.

Greek literature and philosophy (along with the Greek tongue) were fused with these cultures. This process came to be known as Hellenism. But Israel didn’t merely soak up Greek culture-it recognized Greek culture as a “modern” culture and began to reinterpret their own traditional values and culture in light of what the Greeks offered. This synthesis resulted in unique forms of Hellenistic Judaism.

This Hellenism is what led to the translation of Hebrew scriptures in Greek. But these cultural changes didn’t come without static. Many Jews were resistant to Hellenism on principle. So while many countries used Greek as a common linguistic thread between nations, some Jews refused to learn the language.

So you might hear Greek spoken by Jews in Judea and Jerusalem, but you weren’t likely to hear it in Capernaum or other Galilean areas.

Most Romans spoke Latin, so when they had to speak with Jews, they would use Greek. Consider this passage from Luke:

And they began to accuse him, saying, “We have found this man subverting our nation. He opposes payment of taxes to Caesar and claims to be Messiah, a king.”

So Pilate asked Jesus, “Are you the king of the Jews?”

“You have said so,” Jesus replied.

Then Pilate announced to the chief priests and the crowd, “I find no basis for a charge against this man.”

But they insisted, “He stirs up the people all over Judea by his teaching. He started in Galilee and has come all the way here” (Luke 23:2-5).

What language was Pilate speaking here? He couldn’t have been speaking his native Latin because the audience wouldn’t have understood. In the same way, he probably didn’t know Hebrew. The chance that a noble Roman leader would stoop to speak (let alone learn) Aramaic is small. After all, Romans would have considered it an uncultured language that was beneath them. It’s a pretty fair guess that Pilate was speaking Greek to this audience.

Jesus probably would have been familiar with Greek, but it likely wasn’t His primary language.

Aramaic was probably Jesus’s primary language

Most of the non-religious documents and inscriptions discovered in this area were in Aramaic. And this is a critical point. When contracts, invoices, and other normal communications are in a particular language, it’s a strong sign that this was the region’s primary language.

Sometimes we see Jesus’s Aramaic coming through in our Bibles. For instance, Jesus used the word Abba talking about God. This was the Aramaic word for father. In the Sermon on the Mount, Jesus says this: “But I tell you that anyone who is angry with a brother or sister will be subject to judgment. Again, anyone who says to a brother or sister, ‘Raca,’ is answerable to the court” (Matthew 5:22).

Raca is an Aramaic word that means “empty one” or “empty headed.”

In Jesus’s healings, the gospel writers sometimes use Jesus’s exact phrasing. One time when Jesus was healing a deaf man, He looked up at the sky and said, “Ephphatha” (Mark 7:34). This is Aramaic for “be opened.” And at another time when He raised a young girl from the dead, we’re told that He said, “Talitha koum!,” which means “Little girl, get up” in Aramaic (Mark 5:41).

And the most dramatic example comes from Jesus’s words on the cross. As He hung there redeeming us all, Matthew quotes Him as saying, “Eli, Eli lema sabachthani?” which is Aramaic for “My God, My God, why have you forsaken Me?”

Trusting in Jesus’s words

While we can’t be entirely sure what language Jesus spoke the most, we can trust in His words as they have been passed down to us in the Scriptures.

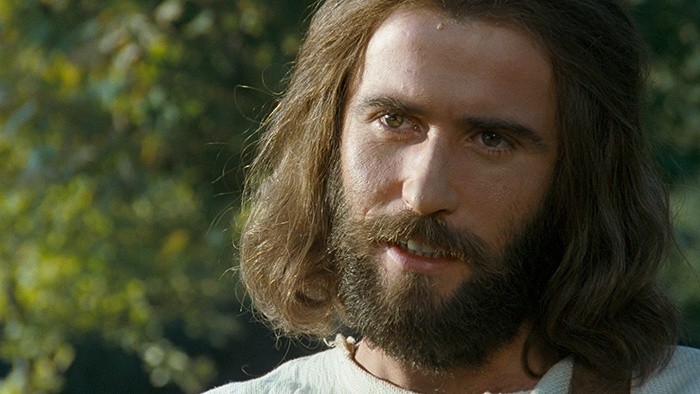

There is a question that’s even more critical than what language Jesus spoke, and that is, “How can we get Jesus’s words to more people around the globe who have yet to hear about our Lord?” This has been the question driving Jesus Film Project® since its inception.

Through the “JESUS” film, we’ve been able to share Jesus’s words in over 1,800 languages, leading to more than a million decisions to follow Jesus!

But our work is not done. We’re still hard at work fulfilling the Great Commission by bringing the story of Jesus to the world. Your gift could help us share the gospel with unreached people in their own language. Would you consider helping us meet this goal?